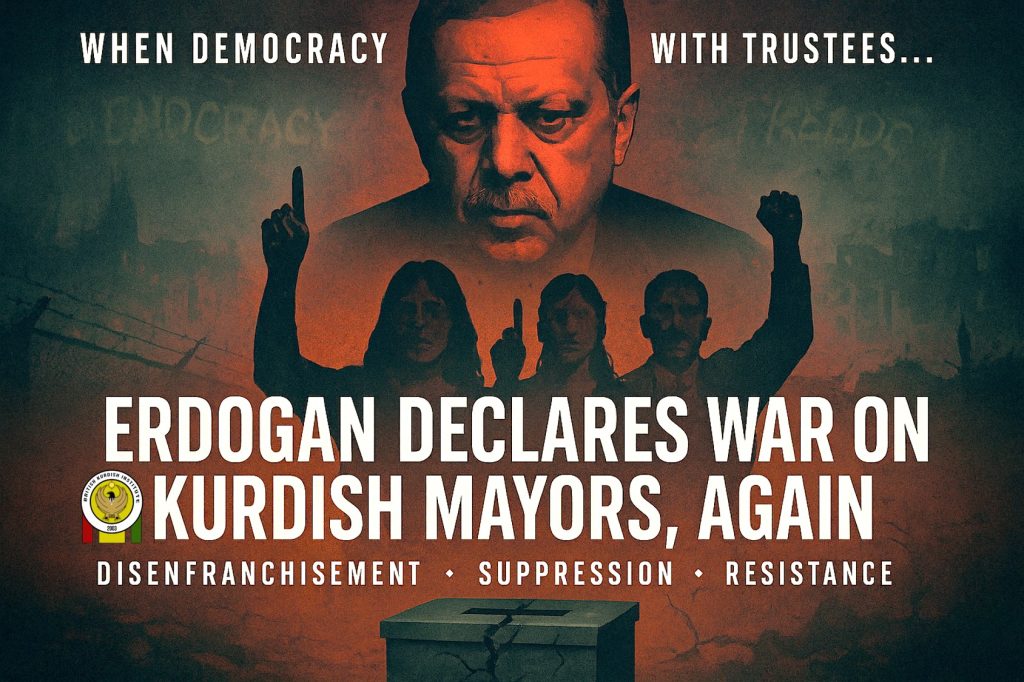

Central Government Removes Elected Mayors

On November 4, Turkish authorities dismissed the elected Peoples’ Equality and Democracy (DEM) Party co-mayors of Mardin, Batman, and Halfeti. In their place, the government appointed “trustees” loyal to the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

So far, four DEM-run municipalities—won during this year’s local elections—have been taken over in this way. This has deprived more than 362,000 voters of the representation they chose at the ballot box. Reports suggest that up to 37 more DEM municipalities may soon face the same fate.

A Long Pattern of Disenfranchisement

Disempowering Kurdish voters has been a signature policy of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan since his government abandoned peace negotiations with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 2015. The removal of pro-Kurdish mayors has devastating effects on the movement’s ability to pursue a peaceful and democratic solution to the conflict.

Today, as the possibility of new peace talks resurfaces, Kurdish politicians warn that continued attacks on local democracy will only deepen mistrust.

Preventing Peace Talks

In October, reports emerged of possible dialogue between the government and Abdullah Ocalan, the imprisoned founder of the PKK. Soon after, far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahceli demanded that Ocalan testify before parliament to end “terrorism” and dissolve the PKK entirely.

Although Ocalan briefly met his relatives on October 23—the first such contact in nearly four years—his communication with the outside world remains cut off. Observers note that Bahceli’s demands are impossible to meet without meaningful state reforms that address Kurdish political grievances.

Why Municipalities Matter

Municipal governments are among the few spaces where Kurdish communities can practice limited self-governance. Since the early 2000s, pro-Kurdish parties have used them to promote participatory democracy, cultural recognition, and truth-and-justice initiatives.

Attacking these municipalities undermines peace efforts. According to the Kurdish Peace Institute, districts where elected mayors were replaced with trustees experienced more political violence than those where election results were respected. Similarly, a Spectrum House poll found that 79% of Kurdish voters believe such interventions make resolving the Kurdish question even harder.

As DEM MP Ceylan Akca explained:

“Strong local democracies are the core of our paradigm. Municipalities and municipal councils allow equal and fair representation of women and minorities. Through equality and shared power, it is possible to ensure societal peace and then regional peace.”

Excluding Women from Politics

Trustee interventions also target women’s participation in politics. Studies reveal that after the 2014 and 2019 elections, at least 132 women lost office when trustees replaced DEM co-mayors. Women’s shelters, child-care programs, and cooperatives promoting gender equality were shut down, erasing years of progress.

A striking case is that of Gulistan Sonuk, the ousted DEM mayor of Batman. She defeated an Erdogan-backed Islamist candidate with ties to the defunct Turkish Hezbollah, notorious for targeting Kurdish activists in the 1990s and 2000s. Sonuk won 65% of the vote, the highest margin in Turkey. Her victory sparked celebrations with chants of “jin, jiyan, azadi”—“woman, life, freedom.”

Sonuk told the Kurdish Peace Institute:

“Since the government could not establish itself in our region, it carried out a campaign against us using these gangs. But the people of Batman, especially women, remember what they did in the past. They supported us and rejected the government’s candidate.”

She added:

“The government could not accept that, in a conservative province like Batman, a young woman like me could win such overwhelming support and defeat their candidate.”