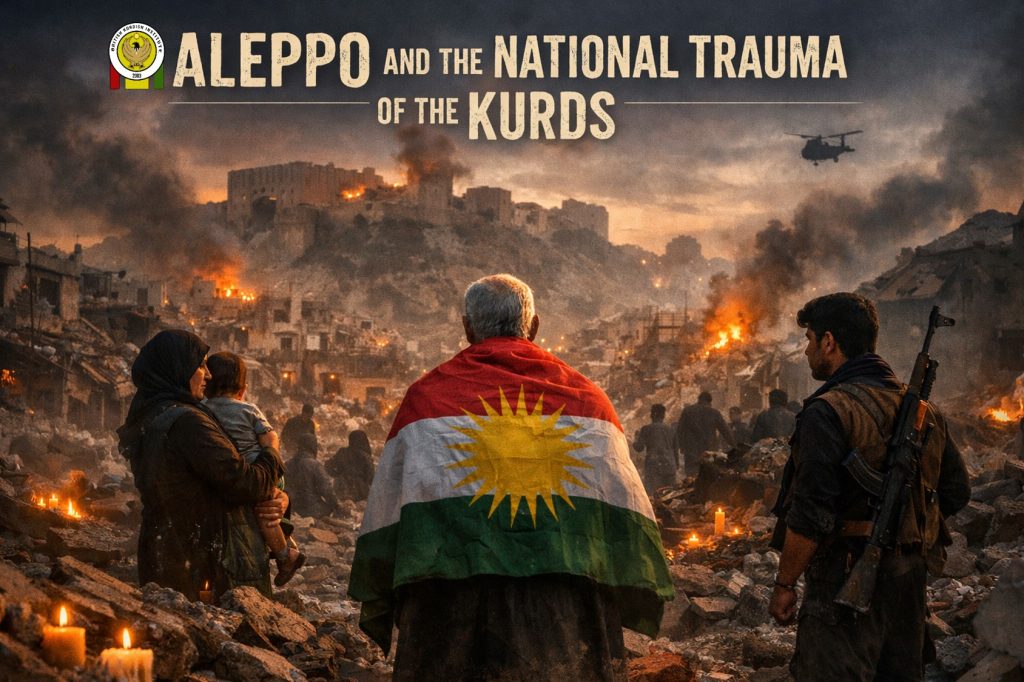

The renewed attacks on the Kurdish neighborhoods of Sheikh Maqsood and Ashrafiyeh in Aleppo are not perceived by many Kurds as just another episode of the Syrian war. They are experienced as something far deeper: the reopening of a national trauma that has accumulated over centuries.

Aleppo today is not merely a battlefield. It is a place where history, memory, and present violence collide. What happens there raises a fundamental question: will Kurdish suffering continue to be treated as a marginal footnote in global politics, or finally be recognized as a profound injury to humanity itself?

A People Without a Nation

The national trauma of the Kurds is rooted in a historical experience that has few parallels. For centuries, Kurds have lived on their ancestral land without ever being allowed to exist as a recognized nation. They have learned what it means to be strangers in their own homeland.

Across Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, Kurdish identity has been systematically marginalized. Speaking Kurdish, practicing Kurdish culture, or openly naming Kurdish identity has repeatedly been criminalized or punished with violence. This repression has shaped not only individual lives, but entire generations.

Permanent Insecurity and Alienation

What does it mean for a people to never live as a nation? It means living in permanent existential insecurity—with no political home, no state that guarantees belonging.

Kurds carry passports issued by states that often deny or suppress their identity. This legal citizenship stands in stark contrast to an inner certainty: Kurdish language, history, and culture are older than the modern nation-states that govern them. The result is deep alienation. One may remain physically present—but never fully belong.

Land, Loss, and Dignity

This trauma is not abstract. Many Kurds describe it in deeply physical terms: the inability to truly touch their land, work the soil freely, or build a future rooted in continuity.

For Kurds, land is not merely property—it is a relationship. A relationship repeatedly destroyed by displacement, burned villages, militarized zones, and borders drawn without regard for the people who lived there. The loss of land is therefore also the loss of dignity, meaning, and future.

Aleppo as Retraumatization

The violence in Aleppo is not a new wound—it is a retraumatization. It echoes a long chain of collective suffering:

the massacres of the 1930s in Turkey, the chemical attack on Halabja in 1988, the Anfal campaign, the genocide against the Yazidis in Shingal, the siege of Kobane, and the war against ISIS, in which more than 12,000 Kurdish fighters lost their lives.

These events do not exist separately. They overlap, merge, and accumulate, forming a collective memory transmitted across generations—unresolved and ongoing.

Anger, Helplessness, and Abandonment

This trauma produces contradictory emotions: anger over continuous injustice, helplessness in the face of political powerlessness, and a deep sense of abandonment. For decades, many Kurds have described themselves as the “orphans of the universe.”

Psychologically, the metaphor is precise. Orphans lack a reliable authority that takes responsibility for them. This is how many Kurds experience international politics—where protection is promised, but rarely guaranteed.

Violence Under the Name of Governance

What makes Aleppo particularly painful is that the violence is carried out by actors presenting themselves as a so-called interim government in Damascus, despite their clear roots in jihadist movements.

The fact that these actors now use diplomatic language does not erase their ideological origins. Terror is being carried out against Kurdish civilians in the name of Syria, while perpetrators gain political legitimacy.

Europe, Complicity, and Moral Injury

For Kurds—and for other minorities such as Yazidis, Christians, Druze, Ismailis, and Alawites—this is a bitter pattern. Perpetrators are politically upgraded, while victims remain unprotected.

Particularly devastating is the fact that the European Union financially supports this interim authority at the very moment Kurdish neighborhoods are under attack. What is framed as stabilization in Brussels is experienced on the ground as a reward for perpetrators—a political and psychological catastrophe.

A Regional Pattern of Insecurity

Developments in Iran and Turkey further reinforce this trauma. Executions, repression, and military control in Kurdish regions, combined with the collapse of peace efforts in Turkey, have led many Kurds to a painful conclusion: they are safe nowhere.

Aleppo is therefore not an isolated tragedy. It is a symbol of a structural condition.

Why Global Decisions Matter Psychologically

International political decisions are not neutral. When survivors see global powers cooperate with compromised actors while victims remain invisible, a deep moral injury occurs. Trauma becomes chronic, trust in law and justice erodes, and resignation sets in.

The message received is devastatingly clear: the world has abandoned us again.

A Call to Europe and the United States

Europe and the United States know what national trauma means. Their own histories—World War II, colonialism, slavery, Vietnam, Afghanistan—are marked by deep moral and psychological ruptures.

Anyone who takes these experiences seriously should understand the consequences of ignoring collective trauma elsewhere. Human rights are not a luxury of stable societies; they are a foundation of human survival.

Trauma, Resistance, and Resilience

Yet Aleppo also reveals another dimension. The violence has sparked a new wave of global Kurdish solidarity. Across borders, generations, and beliefs, Kurds are coming together.

The slogan “Long live the resistance in Rojava” is not merely military—it is a declaration of dignity. A refusal to be reduced to eternal victimhood.

More Than Suffering

The national trauma of the Kurds is not only a story of pain. It is also a story of survival, resilience, and moral clarity. Passed down not only as suffering, but as strength, sensitivity to injustice, and a deep belief in democracy and coexistence.

What is decided in Sheikh Maqsood and Ashrafiyeh is larger than Aleppo. It is about whether ethics and human rights remain universal principles—or become empty rhetoric in a world driven by power and profit.